My son thinks he can do anything. It’s one of his best qualities. He’ll say “yes” to everything with complete confidence that he can do it. However, it’s one of his biggest challenges because there is often a disconnect between what is possible and what is required to accomplish the goal.

It’s one of my biggest challenges, too. When my son says he wants to do something or can do something, my reaction is to sometimes question his ability to dissuade him from wanting to do it or believing that he can.

I think I’m doing it to protect him. I don’t want him to be disappointed when he can’t do something. I don’t want him to disappoint other people who might depend on his ability to do something. I don’t want him to feel like a failure, so I convince him that he can’t do something so that he doesn’t try.

Baseball started again and, at his age level, my son is surrounded by kids who are more athletic, more experienced, and more skilled than him. They already know the intricacies of each position, how and where to move in most situations. While there are a few more dropped balls, errant throws, and wild pitches, it’s like watching a scaled down version of a professional game. The pitches are getting faster, the balls are getting his harder, and the level of competition is higher.

The start of the season was rough. We hadn’t practiced much in the off-season, so it was as if my son had to learn the basics again, while most of the team looked like they never stopped playing. My heart would sink every time my son missed an easy catch or fumbled a ground ball. I felt anxious every time he was on base, worried that he wouldn’t understand his coach’s instructions or be fast enough to get back to the base if the pitcher tried to pick him off.

Despite those mishaps, he showed up every game. He did his best and had great moments of big hits and dramatic defensive plays. His coaches and his teammates were supportive and celebrated his successes, and, above all, he felt like he was part of the team. He was so much a part of the team that, when his coach was talking about giving the players chances at different positions, my son said he wanted to pitch.

My first thought was to talk him out of it. The pitchers at this level were already throwing a variety of pitches. They were shaking off signs from their catcher, giving looks to keep runners close to the bases, and occasionally trying to pick them off. They changed the speed of their windup and delivery to confuse the batters. Imagine a professional pitcher, only shorter. My son does not fit that description.

Instead, I told him if he wanted to pitch, he would have to practice with me every day. The next day, the first thing my son said to me after work was to ask me to go outside and practice. That first time, we measured out the 60′ 6″ distance from the mound to the plate, and it seemed impossibly far.

We started with warmups to get his arm loose, mixing in a few grounders and popups. When he was ready, we pretended it was the bottom of the 9th inning, and his team was leading, and he had to get three outs to win the game.

He stepped onto the makeshift pitcher’s mound, and I squatted at the plate. He went through the motion of his windup, let the pitch fly, and I watched it sail over my head. Our make-believe team lost that first game as he walked batter after batter, but mixed in with the wild pitches were a few perfect strikes.

By the third day, he was throwing more strikes, and rather than losing, we tied and had a wiffle ball home run derby to settle the score (he won). On the fourth day, he walked only two batters before he got the third out. He threw so few pitches that we had to change the story of our game to start in an earlier inning to give him more pitches to throw.

My son talks about those backyard simulations as if they were actual games, causing a few confused looks from his team when he doesn’t give them the context. But the smile on his face after striking out an imaginary opponent filled my heart with joy.

I promised my son that I would reach out to his coach to let him know that we were practicing pitching. But as much as he had improved in the backyard, my fears and concern crept back into my mind. What if he couldn’t deliver in a real game? What if the other kids made fun of him? What if that ruined the joy of the game for him?

Each day I would think about contacting his coach, and each day I would convince myself not to send the message. But it felt wrong, not only not honoring the promise I made to my son, but because I knew these were my obstacles, not his, that were preventing me from taking the next step. I had to trust that the coach would make the right decision and would be able to navigate the situation in a way that wouldn’t catastrophize the situation and hurt my son’s heart.

I typed out the message, trying not to lower the bar too much. I said that my son has been practicing his pitching every day, and if there were an opportunity in practice or an upcoming game, he would like to give it a shot. “Ok” was the only response.

A few days later, at our next game, we were short a few kids, and the score matched our player deficit. I’m not sure who initiated it, but toward the end of the game, my son came over to tell me that he was going to pitch. I smiled and said, “Awesome!” but inside, I could feel my body tense up—the moment of truth.

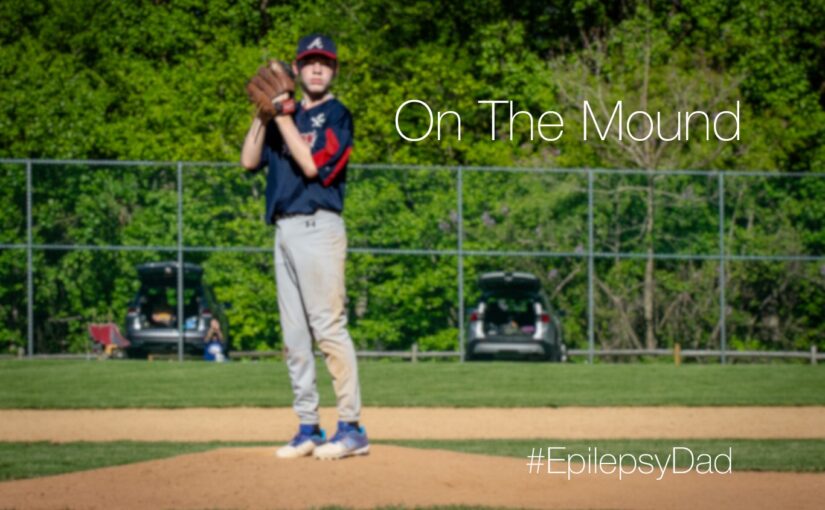

I watched as he warmed up with another player and was pleasantly surprised that he reliably got most of his pitches to the catcher. With only a few innings left, the coach told me that unless we scored a bunch of runs before the last inning, my son would go in. We did not score those runs, and I watched in slow motion as my son stepped through the gate to the field and took the mound.

I had one of those moments where I wondered whether my presence was helping or hurting. He would look at me after every pitch, but I couldn’t tell if he was looking for my approval, guidance, encouragement, or support. But he was on the mound. He was pitching. And, while there were more than a few pitches that got past the catcher, there were just as many that sailed over the plate.

His pitches weren’t fast, so there were a few big hits. He walked a few batters. But he kept stepping back on the mound. His teammates fielded a grounder and got the first out. My son snagged a scorcher right back to him as casually as I’ve ever seen him field a ball and made the throw to first for the second out. And then, after being up 1-2 on the pitch count, the last batter hit a soft grounder to first for the final out. My son had pitched a complete inning.

“Awesome,” I said again, and I met him on the field. It was awesome, in the literal sense of the word. I was in awe of his dedication to his goal, his bravery in stepping into the unknown, and his willingness to have doing his best be enough.