As parents, we have to figure out what lessons we want to teach our children. The balance of our “when I have my own kids, I will/will not” promises are finally called due. We get to decide what to keep from our own childhoods and what to throw away. But knowing what to keep isn’t always clear and, worse, it can be terrifying. It involves shifting perspective enough to question some fundamental truths.

When I was growing up, I never thought anything I did was good enough. I took little joy from what I achieved because there was always someone who did it first, faster, or better. There was always room to grow. Accomplishments were expected but rarely celebrated. Humility was a virtue and pride was a sin. These messages became the foundation for how I felt about myself and how I lived my life.

It wasn’t always obvious to me that this part of my philosophy wasn’t something that I wanted to pass on to my son. After all, I turned out okay. I am humble and grounded. I’ve had amazing experiences. I have a good job and the best family. Knowing that there is always someone better means striving to work harder, to learn more, and to do better. It made me a perpetual student and a life-long learner.

This spirit of growth and learning is one that I want my son to have. But before he started having seizures, I wouldn’t have thought to teach him that lesson in a different way.

I remember sitting by his bedside in the hospital. The dark room was lit only by the light coming from the EEG monitor that showed constant, wild activity. His body had gone toxic from a bad reaction to one of the medicines we hoped would stop his seizures. It didn’t. The seizures raged on, and the toxicity left my son immobile, ataxic, and unable to form thoughts or words. I felt helpless. I was afraid. I prayed. This lowest of points stretched on for days.

When he could start to form words again, it was the most amazing thing I had ever seen, and we cheered. When he could hold his frail body up by himself, we cheered. When we left the hospital, even though our boy was not quite himself, it was another cause for celebration. With each milestone he passed, we cheered. If he stumbled, we acknowledged how hard he was working. There was no “but”. “But, you used to be able to do it better.” “But, those other kids are faster.” For the first time in my life, I saw what it meant to work hard and to do your best and for that to be enough. “That was great, buddy. You worked so hard to do that. I’m proud of you.” Full stop.

I hate epilepsy. I hate what it does to my son. But I would hate myself if I didn’t learn the lessons that this experience is teaching me. I don’t want to raise a child that always gets a trophy. But I also don’t want to raise a kid that thinks there is a trophy for everything and that he never gets one. I want him to be proud of doing the best that he can. That should be a good feeling, not one that should lead to shame. Epilepsy showed me how dark things can be, and these moments of grateful hope and joy can shed a little bit of light.

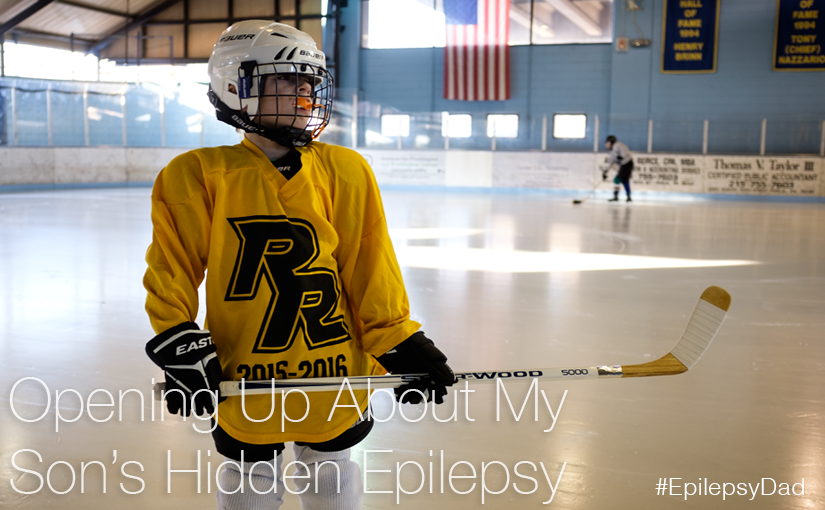

It turns out that this approach has led to my son working hard and liking to learn new things. Except he feels good about where he is. He is also braver than I ever was, willing to try new things outside of his comfort zone. He’s also a good sport and as grounded as any 7-year-old should be. Those qualities that I had hoped to pass on to him are there. Except his motivation isn’t based on feeling less than everyone else. His motivation is based on being the best him that he can be and being able to feel joy in that.

Before you feel bad for the other little boy in this story, this experience has taught me the same lesson. In celebrating my son’s accomplishments, I’m starting to acknowledge my own, too. Just a little. But I’m doing the best I can.