There are still days when I think that this is all temporary and that my son will someday outgrow his condition. The medicine, and the side effects, and the diet are all short-term measures that we are only doing until his brain sorts itself out, and then we can stop them altogether. These inconvenient years can become a distant memory.

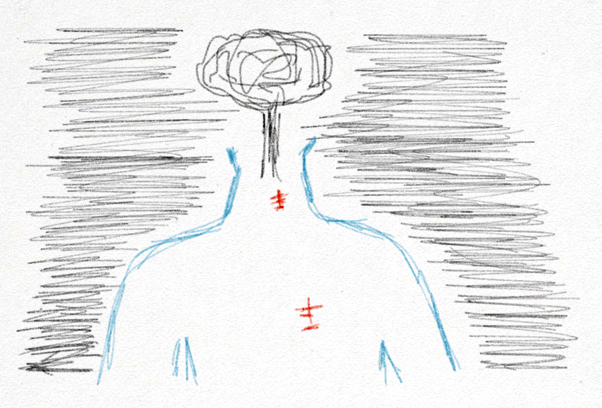

Holding on to that fantasy is partly what made me reluctant to agree to VNS surgery for my son. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is a technique used to treat epilepsy that involves implanting a pacemaker-like device that generates pulses of electricity to stimulate the vagus nerve. In theory, this stimulation can be tuned to disrupt my son’s brain’s bad habit of firing all its neurons at the same time in uncontrolled bursts, which is what causes a seizure.

There is a sliding scale of expectations with the VNS. Best case, it helps manage his seizures and we can revisit his medications and the ketogenic diet. Next best case, it helps regulate the break-through seizures he is still having. Worst case is the same worst case as every new treatment we try…nothing happens. Except, of course, for a list of new risks and side effects, both from the surgery and from the stimulation. Tingling, numbing, an altered voice, headaches, difficulty swallowing or breathing, just to name a few.

But it wasn’t just the risks that made the decision difficult. The surgery feels more permanent. They’re going to cut in to my son and insert a box with tiny wires wrapping around a nerve that leads to his brain. Once they cut him, he cannot be uncut. Even if we remove the box and wires because the seizures do go away some day or because it doesn’t work, he will have a scar to remind him of the hardships that he had to endure at such a young age. There will be no room for denial or pretending that none of this happened.

Because it is happening.

Whether we have the surgery or not, whether it works or not, this is our reality. As I struggled with my decision, another epilepsy dad told me that we should do whatever we can to help our children. Whether it works or not, if there is a chance that it can make their lives better, it’s worth it.

In the end, that has to be enough. To keep hoping for a better life and to keep trying things, even following failure after failure. Accepting the idea and agreeing to the surgery is another in a long list of impossible choices.

We scheduled the surgery, but I wake up every day wanting to call it off. To keep my son whole. Time and his condition, however, are quickly taking aware that option.