This post is part of the Epilepsy Blog Relay™ which will run from November 1 to November 30, 2017. Follow along!

I remember the first time I saw a Van Gogh painting. I mean, really saw a Van Gogh painting. I stood in front it the same way that I’ve stood in front of each of his paintings that I have seen since. I wondered about him. About his life. About his painting. About his anxiety, synesthesia, and depression. About how it all came together in brilliant color on a piece of canvas.

That was long before I knew that he had epilepsy or how much of an impact epilepsy had on his life. And on mine.

When my son was first diagnosed with epilepsy, I did what I imagine many parents do. I went to Google and searched for famous people with epilepsy. I needed to see examples of other people from history that were able to succeed in spite of their condition. I needed to know that the endless possibilities that my son came into the world with were not taken away because of the faulty wiring in his brain. I needed some hope for his future and I thought the way to find it was by looking to the past.

That my search brought me closer to Van Gogh was a bit of a mixed bag. On one hand, to learn that my favorite painter had the same condition that my son has was an incredible coincidence. When I look at one of his paintings now, I wonder how much of his epilepsy shows up in them. How much of the way that he saw the world was due to his epilepsy?

As I wrote this post, I pulled up an episode of Dr. Who where he visits Van Gogh. There is a scene where Van Gogh, the Doctor, and his companion, Amy, are lying in a field looking at the night sky. Van Gogh explains the colors that he sees and the wind in the stars and the sky transforms into one of Van Gogh’s most famous paintings. It’s hard to look at a painting like Starry Night and not think of the auras that some people with epilepsy see. Will my son see the world as beautiful as this?

“I’ve seen many things, my friend. But you’re right. Nothing’s quite as wonderful as the things you see.” ~Dr. Who

On the other hand, knowing what I did about Van Gogh’s life and how it ended filled me with dread. Did epilepsy or the medications he was on cause any of his other conditions or make them worse? Did it contribute to him taking his own life? I’ve met people with epilepsy who battle depression and I’ve read about people who lost that battle. Is that what lies ahead for my son? He’s only eight.

In the episode of Dr. Who, the visit from the Doctor is in the same year of Van Gogh’s death. In one of the final scenes, the Doctor takes Van Gogh to the present to show him what becomes of his work. The art curator describes Van Gogh as someone who “transformed the pain from his tormented life into ecstatic beauty”.

The Doctor and his companion return Van Gogh to his time and he seems refreshed. But when they return to the present, they learn that their visit did nothing to rewrite the past.

“The way I see it, every life is a pile of good things and bad things. The good things don’t always soften the bad things, but vice versa, the bad things don’t always spoil the good things and make them unimportant.” ~Dr. Who

While they were able to give him a few more good things, the bad things in Van Gogh’s life were still too much.

When I started this post, I wanted to write about epilepsy and creativity. I wanted to highlight Van Gogh as an example of someone who created amazing things in spite of his epilepsy. Or maybe because of it. I wanted to talk about my son and how he has an amazing imagination and an openness to share the way he sees the world.

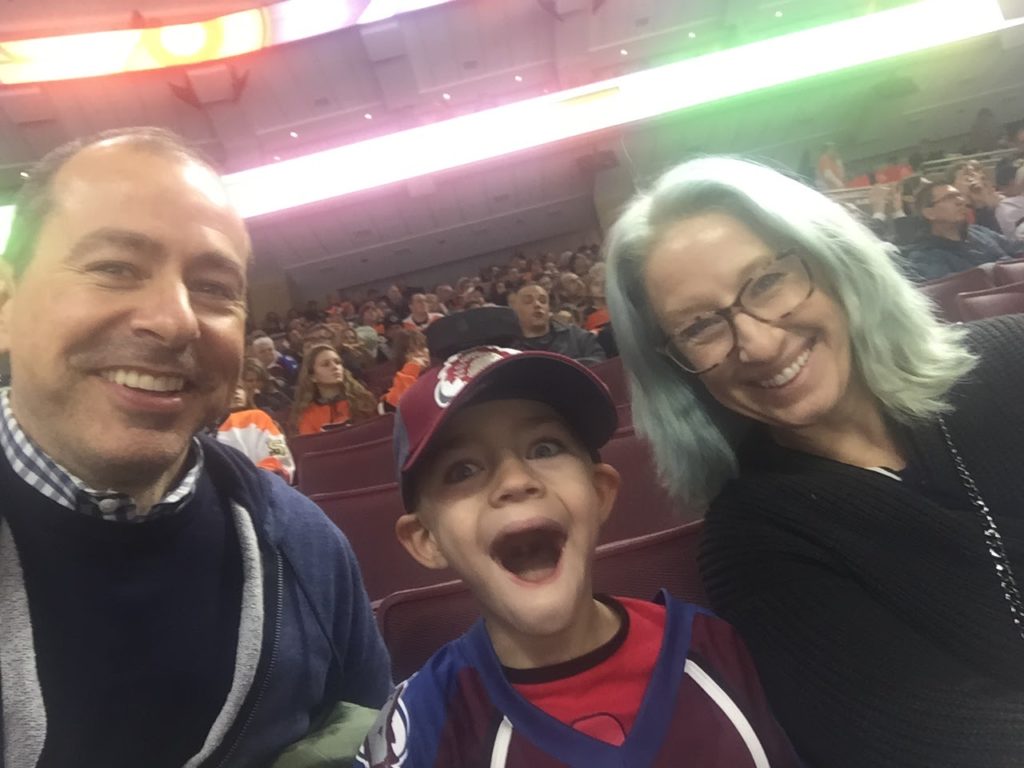

But every life is a pile of good things and bad things. When I see my son’s anger rise or his mood darken, I sometimes think of it happening as a teenager or a grown man. I think about the years of seizures and medications and side effects ahead of him and I crumble.

But he is only eight. There is no way of knowing what is in store for him. So instead of letting the bad things spoil the good, it’s up to me to encourage my son to share the way he sees the world because there is beauty in that. Because there is beauty in him that the world needs to see.

When I was finishing this post, I had the episode of Dr. Who on the screen for inspiration. My son walked by and asked what I was watching, and I told him all about Van Gogh. I told him that he was a brilliant painter who also had epilepsy. I said that he saw the world in a different way and used paint to show the world what he saw because he was an artist.

My son smiled at me and said “That’s so cool. I’m an artist, too.”

NEXT UP: Be sure to check out the next post tomorrow by Leila Zorzie at http://www.livingwellwithepilepsy.com. For the full schedule of bloggers visit livingwellwithepilepsy.com.

TWITTER CHAT: And don’t miss your chance to connect with bloggers on the #LivingWellChat on November 30 at 7PM ET.