Life’s challenges are not supposed to paralyze you, they’re supposed to help you discover who you are.

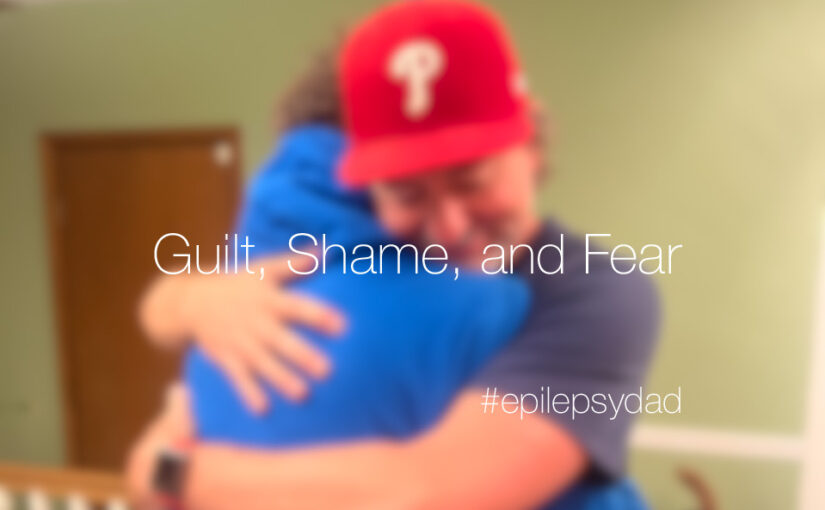

When my son started having seizures, I was paralyzed. I was afraid. I was helpless. I was there physically but didn’t know how to be emotionally present for him or my wife. I had disassociated from the situation, leaning into my job and the mechanics of keeping a household running. My wife became the full-time caregiver in a new city without any family to support her through my son’s most challenging times medically, intellectually, and emotionally.

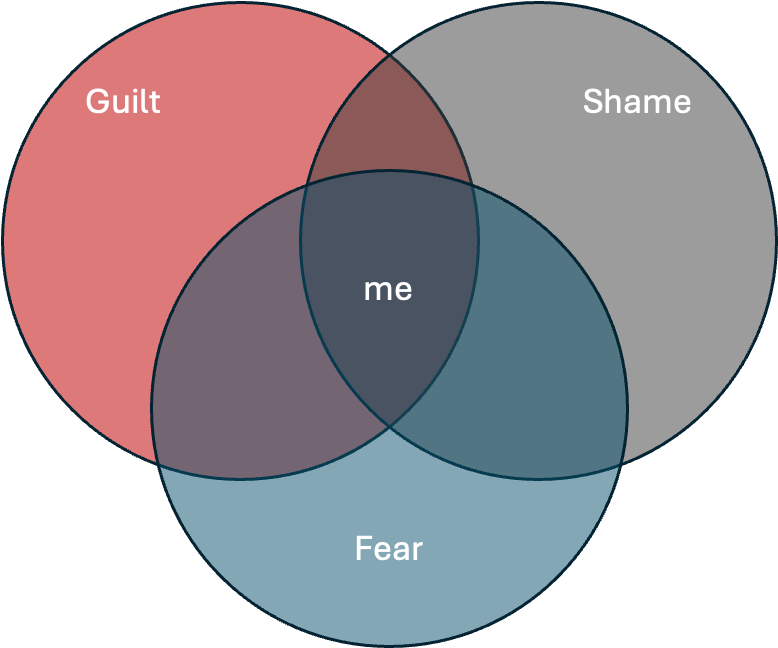

After years of therapy, I still struggle with the semantic debate about whether to say I was afraid or I felt afraid. But looking back, I think I was both because while those words described how I was feeling, they also described my actions. And inactions.

It was an impossible time, and I committed to doing better. Over the years, I became a better partner and father, but I had a lot of work to do to repair the damage those years did to the relationships in my life.

A few years ago, my wife had health challenges that limited her capacity for physical activity. Rather than distancing myself from the situation, I tried to lean in. In addition to going to work, I took on most of the responsibilities around the house. I thought showing her I could care for her would be enough. But the same lack of emotional connection persisted. She was cared for but wasn’t receiving what she needed and deserved most.

Being the parent of a child with special needs is challenging enough. Coming into the situation with trauma and fears makes the situation infinitely more complex, dangerous, and demanding. I know families who have been ripped apart by it. I also know families who have become stronger, and I wanted to be one of those families.

Rather than paralyzing me, I want these challenges to help me discover who I can be. I want to be the type of person who can show up and be present. I want to be a person who can be vulnerable when the vulnerability is needed. I want to be the type of person who makes a person feel seen who is struggling, or in pain, or needs to feel seen. I want to be the type of person who isn’t afraid to be seen.

I still have moments of doubt, of fear, of wanting to retreat into old patterns. But each time, I remind myself that being present, vulnerable, and truly showing up is a choice. And every time I make that choice, I get closer to the person I want to be.