Lately, my wife and I have started a new routine. We sit next to each other on the couch, flip open our computers, pull up our calendars, and look at the week ahead. Even though it’s all digital and we share our calendars, it gives us a chance to get on the same page. We can add any events that we miss or decide who is picking up dessert for dinner at a friend’s house later in the week. But it also gives us a chance to create a manageable week for our son.

Fatigue plays a big part in the frequency and severity of my son’s seizures. If he gets too mentally or physically taxed, they break free from their confinement. Instead of happening only in the morning, he’ll have them during his nap or after he goes to bed at night. The more seizures he has, the less rested he is, which causes more seizures. It’s a cycle that we work very hard to avoid.

In most cases, that means we only plan one activity a day. While other kids his age go between team practices, play dates, and birthday parties, he’ll do one thing. Instead of “and”, our lives involve a lot of “or”. A birthday party or a movie. The museum or the park. A play date or a baseball game.

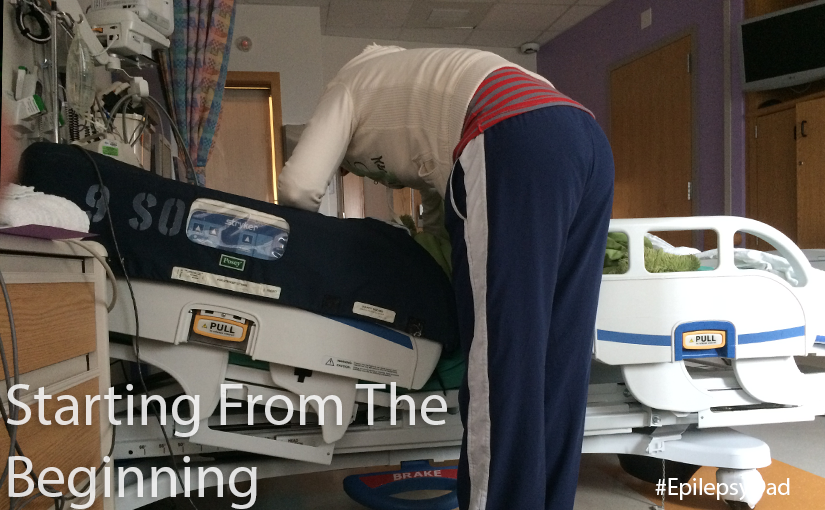

Some days, that one thing is school. Other days, that one thing is therapy. Those activities are so draining to him that, if he goes in already tired, he can barely function. We see that, too, when he leaves school early to go to one of his appointments. But on those days, we don’t have a choice. He wills himself through it but then he stays exhausted through the next day. If that happens, we adjust his schedule to try to prevent those demanding days from adding up. If we can’t, or if we miss the signals that he’s running on fumes, we lie next to him in bed, watching him pay the price.

We had a few of those nights in early summer. School was ending and we tried to juggle therapy and baseball practice. He loved baseball, but it broke my heart to see what the physical exhaustion did to him at the end of the night. It was all too much, but deciding what to cut and when was impossible. School is important and provides social opportunities. Therapy helps rebuild those skills that he lost and reinforce those that he will need. And baseball…baseball made him feel like he was part of a team. And that he was a normal kid.

I wanted to take this post in a positive direction. I wanted to say that “in lives packed with activities and distractions, having to choose what to do helps clarify what is important.” I do believe that, but I also hate having to decide what to take out of my child’s life. I hate having to limit him in any way. To have to pick one thing. For every day. Every week. Every month. With no end in sight. There is no positivity in that.

But as conflicted as I am, it has inspired me to try to make that one thing amazing and special. And I try to be mindful, present, and grateful for that one thing. Because I know that, no matter how much it hurts, one thing is better than nothing.