Imagine we are sitting at a table across from each other. I’m trying to teach you a complicated concept. Except I don’t understand the concept, either. And I’m also trying to teach it to you in another language. Except neither of us speaks that language. And the room we are in is pitch black.

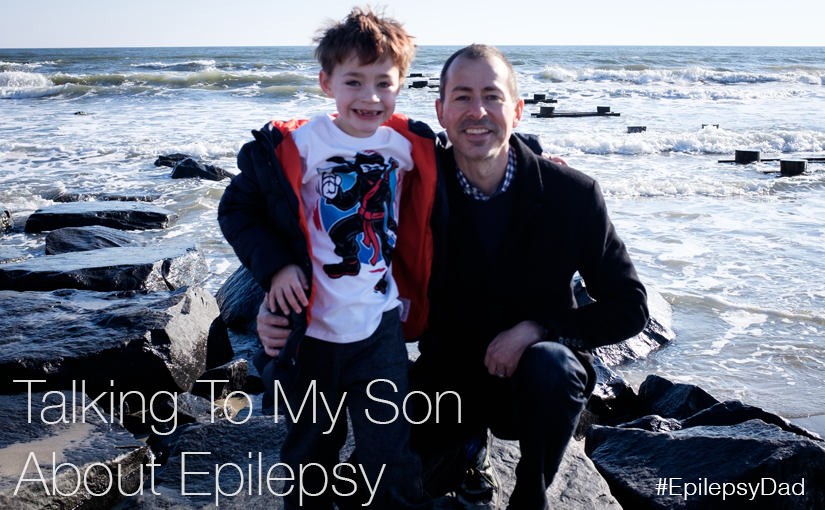

That is what it is like to talk to my son about epilepsy. It’s a topic that I didn’t have a reference for until it entered our lives. I’m learning what it means to be the parent of a child with a disability, but not what it means to have epilepsy. My son has a different perspective. He knows what it feels like to have epilepsy, but he doesn’t have the words to always share what he is going through. He doesn’t remember his life before seizures enough to describe the difference. So we fumble as we try to connect and create a shared experience.

Occasionally, I’ll be able to pull something out of my growing knowledge bank to share with him. A few weeks ago, we strolled through Caesar’s Casino in Atlantic City. We passed a statue of Julius Caesar and I mentioned that he ruled the Roman Republic. I also mentioned that he had epilepsy. “He had epilepsy and he ruled the world, ” I said, “so you can do anything that you want to do.” I skipped the part about Julius possibly suffering from migraines and not seizures. The opportunity for bonding was more important than proven historical accuracy.

There are flashes of a connection, but not enough of one. Epilepsy and seizures will affect him for the rest of his life. History lessons might be inspirational, but they don’t explain what he is feeling and why. They won’t build his epilepsy vocabulary. They might keep him hopeful, but they can’t predict what it will be like for him in the future. Nothing can.

As a father, it makes me feel helpless. It’s my job to protect him. It’s my job to teach him the ways of the world. I think that if I do more research, if I learn more facts, that I’ll somehow be able to forge a path for him. If I can’t make him better, I at least want to make his life easier. But without knowing what he is going through, I’m never sure I’m doing the right thing. What I can do, and what helps me balance my frustration, is loving him and making him feel secure.

Sometimes, there is light in the room. I’m able to see how brave he has become when he tries something new, talks to people, or jumps fifteen feet into a ball pit. I see how hard he works to do basic tasks and how much harder he has to work to do the things he likes doing. There is enough light to see that our family is around the table, trying to connect with each other. We’re still not speaking the same language, but there is enough light to see that we’re in this together.