When I was growing up, there was a family across the street from us that had two boys. One was my age, the other a little older, and they were both part of our neighborhood pack that would play baseball and football in the street, ride around on our bikes, or simply hang out in one of our yards. The younger boy and I, being closer in age, also shared an affinity for computers. His powerful Amiga had better games, so we would spend time at his house playing them, often for hours at a time.

I remember their dad being really strict. They would address him as “sir” and had to ask his permission for everything, from a can of coke to going outside to play. I could often see a look of fear on their faces when they interacted with their father, and I never knew what that was about until one day when my friend took a soda without asking. We were in the front room on the computer, and his father dragged him to the back of the house. As I sat there, I could hear my friend apologizing through the muffled sobs that echoed down the hallway. I heard the unbuckling of a belt followed by the crack of a whip and then more cries. After a few minutes, there was silence. My friend returned to the front of the house and told me that he couldn’t use the computer anymore and that I had to leave. His eyes were still wet. I couldn’t see him, but I knew my friend’s dad was listening, just out of eyesight. I stood up and left quietly.

I was probably thirteen when that happened and, in the years that followed, I watched as my friend continued to wrestle with his relationship with his dad. I could see it worn on his face, but he often shared how he desperately tried to please his father but always seemed to come up short. It was his failure, he would say, and not the unrealistic or inappropriate expectations of his father. I could see him starting to respond more with his own anger. His grades went down, which only made things worse between him and his father. He started to pull away, hanging out with different friends, until I stopped seeing him altogether.

After I moved away, my mother would occasionally give me updates. Unsurprisingly, my friend turned to drugs in high school. I’m not sure if he graduated, but this bright kid who could have done amazing things with computers burned out and gave up. My mother would see him every once in a while, usually at his father’s house after another stay at rehab. She said he was always polite, calling my parents “Mr.” and “Mrs.”. Each time, I would hope that he had finally sorted his life out, even as I wondered why he kept returning to the place that likely was the catalyst for the direction his life had taken.

As much as I hoped his life would take a different path, it never did. He was 33 when he died of an overdose. I couldn’t help but think that his death was the finally, unforgivable mistake that he would ever make and that it was the last in a long line of disappointments to his father. My friend spent his life never feeling like he could please his father. And then it was over.

I haven’t spoken to him since, but I sometimes think about my friend’s father. I wonder if he feels any responsibility for what happened. I wonder if he would change the past and how he treated his son. Sometimes, I wonder if I am making my son feel the same way.

The other night as I was putting him to sleep, my son said that he was sorry for making so many mistakes. It was a gut punch that came out of nowhere. My chest tightened up. I thought of my friend and his dad and I didn’t know how to respond. His comment was like an arrow that struck the bullseye of my greatest insecurity.

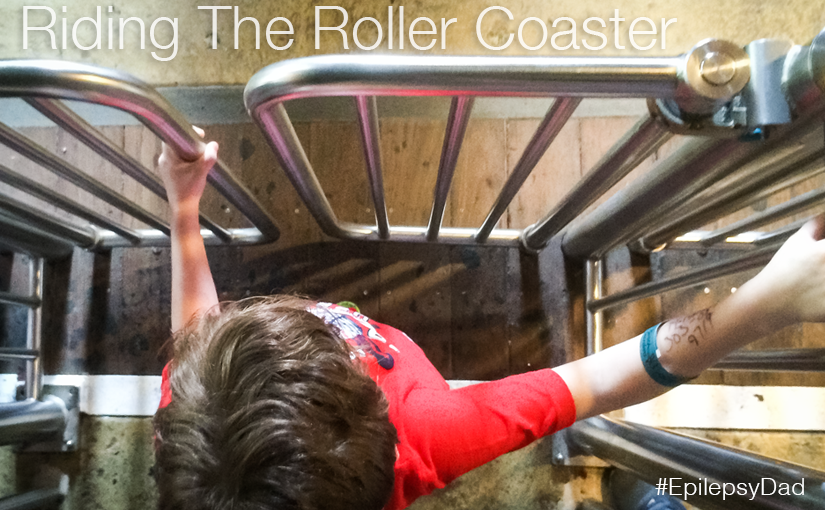

I feel like I’m always riding my son. Sometimes, it’s for normal mistakes that kids are supposed to make. Other times, it’s for things he can’t control because of the side effects of his medicine or seizures, or other complications caused by his condition. He struggles with attention and impulse control issues every day and, as hard as that must be for him, it must be even worse because I am constantly saying “no” and making him feel like he is always doing something wrong. I push him towards perfection because I think it will make his life easier if he can overcome his obstacles, but I am setting extremely unrealistic and unachievable expectations and setting him up for failure. And so I found myself lying next to my six-year-old who is apologizing for being a kid…and human. I don’t need to raise my hand like my neighbor’s father did to do the same type of damage.

I reached out and put my hand on my son’s shoulder. “We all make mistakes, buddy. It’s a part of learning and growing. If we didn’t make any mistakes, then we wouldn’t learn anything new. I make mistakes all the time. I must have made a hundred mistakes today.”

He rolled over and turned to me. “You did?”, he asked. “Like what?”

I laid down next to him and draped my arm over his shoulder. “Well, ” I said, and then I told him about the mistakes that I made during the day. I told him about what I learned from making them and that I was happy that I learned something new. We talked for a while (there were a lot of opportunities to learn and grow that day) until I saw his eyes get heavy. As he drifted off to sleep, I hoped that by sharing my own mistakes, he would see that everyone makes them and not feel so defeated. It was also an opportunity for me to reflect on those mistakes that I made, including how I responded to my son, so that I, too, could forgive myself, and learn, and grow.

My wife had a great idea and I think we are going to start doing it. We have a nightly routine where we talk about out day…something good, something bad, something we are grateful for. We are going to add a mistake that we did today and what we learned.

And then we’re going to celebrate it.