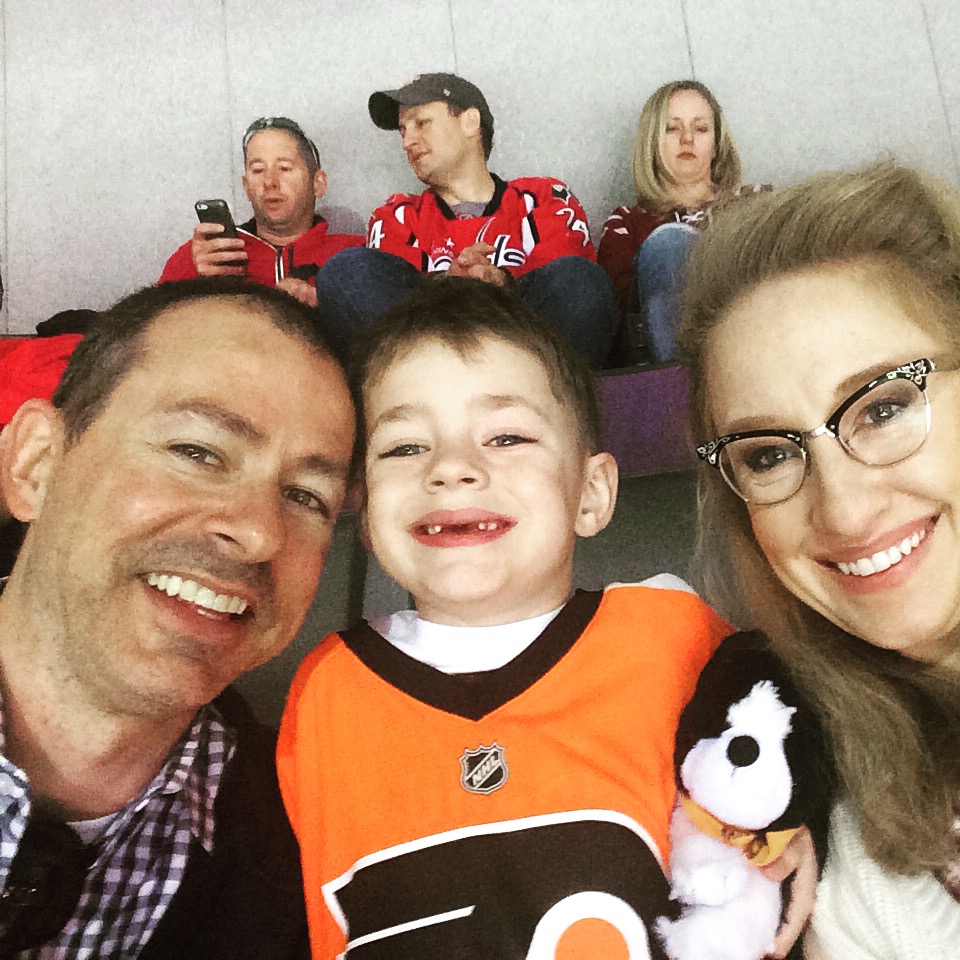

Last weekend, we were in Washington D.C. for the Epilepsy Foundation walk. We had planned the trip for months, and we tucked away some money to pay for the trip and activities while we were there. As it happened, there was a playoff hockey game in D.C. on Saturday night. It wasn’t something we planned on, and hockey tickets are expensive…playoff tickets more so.

I called my wife and told her about the game. “We should do it,” she said.

There was a time in my life where I would have argued. Where I would have tried to rationalize the cost, and crunch the numbers, and adjusted the budget. My wife tried for years to teach me the value in making moments matter, but I had a hard time listening or believing her until my son got sick.

The past few years have been an endless struggle to control his seizures, switching medicines, managing side effects, and behavioral issues, a difficult diet, and the stigma of having epilepsy. Some days, he can’t control his body, or he seizures at night and has an accident. He wakes up some days wanting to give up, or comes home from school embarrassed because someone laughed at him for drinking oil with his lunch. It’s an impossible life for a six-year-old.

Moments don’t need to be expensive or cost money at all. As we walked down the National Mall, he was just as happy playing tag and hide and seek on the grass, and doing the scavenger hunt in the hotel. I could have said I was tired, or that I wanted to see the sights. But those little moments of playing his game and giving him an opportunity to feel normal and to simply have fun matter, too.

But hockey is one of those things that my son hasn’t given up on, and the universe was sending me a message by putting a playoff game in the same city where we would be and, to be sure I wouldn’t miss the message, the game was also against our home team. We bought the tickets and surprised him with the game.

Even though our team didn’t win, the home crowd appreciated his enthusiasm and pat him on his head as he cried in to his hands after another tough loss. As we walked out, he had a smile on his face and moved the home team up on his favorite team list.

I’m grateful my wife has tried to teach me to make moments matter.

And I’m glad I finally listened.