My wife joined a band last year that plays regularly at different restaurants and venues in our area. My son and I try to go to every show, taking in a set or two as we have dinner together and watch our matriarch do what she loves to do and does so well.

A few weeks ago, I was waiting for my son to finish getting ready so we could go to a gig. I was wearing a T-shirt with her band’s name and jeans. My son came around the corner sporting blue jeans, a black on-brand Marvel shirt, and a bright red blazer on a hanger over his shoulder.

“Nice,” I said as we headed to the car.

After we parked, my son stepped out of the car and pulled his jacket from the hanger over the back seat. He slid each arm in turn into the coat and buttoned a single button below his chest, and we headed in.

When we entered the venue, my wife saw her tall, handsome son sporting a bright red blazer. She came over, gave him a big hug, and told him how good he looked. She brought him to the stage, and I played paparazzi, taking pictures of the dapper gentleman and the singing star.

We made the rounds to greet the band, and each of them commented on how tall my son was and how sharp he looked in his jacket. At our table, the waitress also mentioned his blazer, and I could see him carrying himself more confidently and maturely. Sitting across from me, he looked five years older.

The clothes make the man.

“Man.”

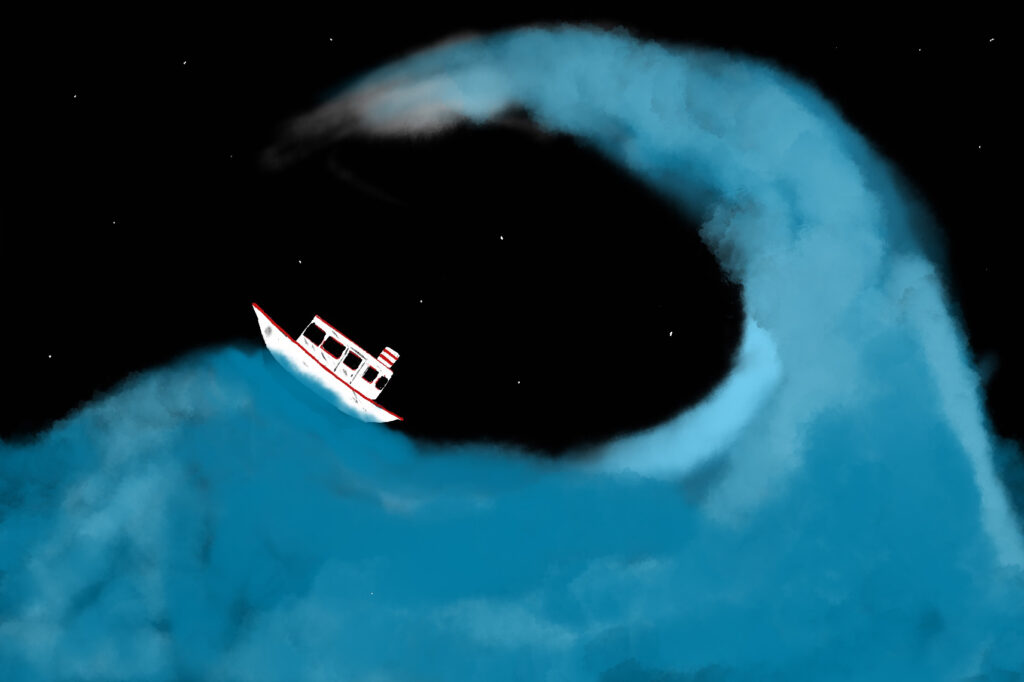

It’s such a loaded word. He’s the size of a man and wears men’s clothes, but inside, he’s still the same boy who, for many years, would go to every doctor’s appointment in pajamas or a costume. I watched his face as he sat at the table obsessively struggling with a Rubik’s Cube. His brain wouldn’t let him stop, but it wouldn’t help him remember or apply the techniques to solve it.

The gap between his outward appearance and his internal workings continues to widen, as does the gap between his development and that of his peers. These gaps are getting harder to reconcile, and they stoke my fear of him being misunderstood by the outside world. I try my best to push those fears away as he looks up at me. I smile, and we talk about his strategy to solve the puzzle and listen to my wife’s voice fill the restaurant.

After dinner and between sets, we said goodbye to my wife. She again commented on how good my son looked in his jacket, and I saw him stand a little taller. He carried that height from my wife’s table and the door, growing even more as a handful of random patrons also commented on how good he looked in his red blazer.

“I feel like a celebrity,” he said as we stepped through the door. In addition to his bright red blazer, he wore a priceless, confident smile.

As we walked to the car, I couldn’t help but marvel at how much that red blazer seemed to transform him—not just in how others saw him, but in how he saw himself. For a few hours, he wasn’t the boy with special needs or the countless doctor’s appointments. He was the tall, confident young man turning heads and making impressions.

While I know the gaps will always be there, that jacket gave him a taste of a world where he could be seen without his struggles, even if only for a little while.