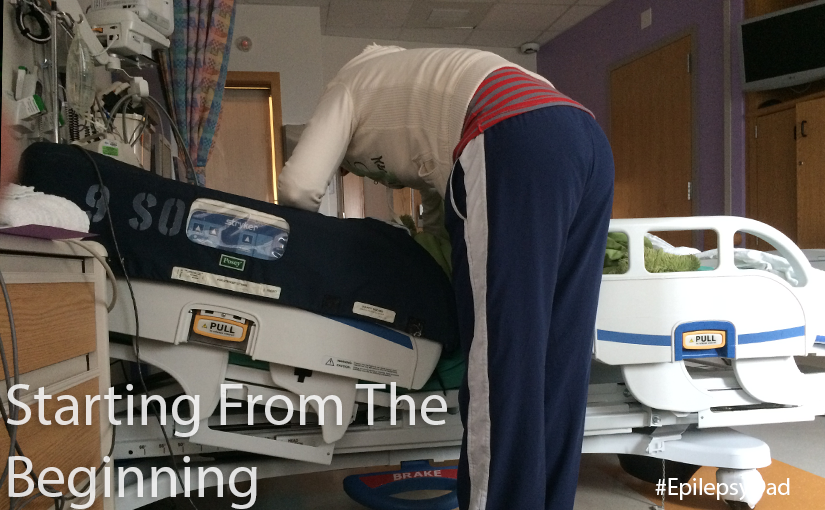

One of the truths about anyone new coming into our lives today is that they will never know how bad things were. Eventually, anyone that hangs around long enough will hear my son’s story. We will tell them how dark the times were and how sick my son got and how grateful we are to be where we are. But looking at my son today, it’s hard for most people to believe that things were that bad.

That disconnect feels isolating. It’s a reminder that there aren’t many people in our lives from that time. We were largely confined to the hospital after moving to a new city. The only people we knew were the medical staff, but they were transitory. We rarely saw any with regularity. Instead, we repeated my son’s history to every new face we saw. But they moved on and we stayed trapped in our world scared, desperate, and alone in the dark. Every day, every week, every month.

Sometimes, when you tell a story over and over again, it can dull the pain. The repetition has a numbing effect that makes it easier to deal with. But when you’re in the middle of it, that doesn’t work. Instead, it keeps the pain and the fear fresh and present. After months of unrelenting confrontation with our new reality, I wanted it to stop. I wanted one person, just one person, who I felt knew us, knew my son and could understand.

After a long string of random faces, my wish was finally answered. One neurologist started coming back through on rotation. Instead of repeating our son’s entire history each time, we could give her updates. She provided consistency and stability through our endlessly repeating days. I began to feel like I was talking to someone who understood what we were up against. Someone who knew how bad things were. She cared about us. Without those connections, it’s hard to imagine anyone fighting as hard as we were to not go back to that place. But she did. And for the last three years, we’ve had her at our side every step of the way.

Until now.

The woman who in many ways saved my son is leaving. I’m trying to be stoic. I’m trying to be grateful for everything she did for us. I’m trying to be happy for her as she pursues more of a focus on epilepsy because of her experience with my son. I’m trying to think about the many more children she is going to be able to help. But I mostly feel afraid. Afraid to take these next steps without her. Afraid that no one is going to get us or my son like she did. Afraid that no one is going to fight as hard as she did because of how connected she was to our story. When there aren’t many people that can relate to what you are going through, the loss of one is significant.

We’re at one of the best children’s hospitals in the country. Our new neurologist is one of the best in that hospital. But she didn’t see my son at his worst and I’m struggling with whether that matters. Whether she’ll fight as hard as she would if she had seen him back when this all started. Whether she will be personally invested in his outcome. Because I need that. I need his caregivers to have that connection to him. I need them to know and call him by his nickname. I need them to know how important he is. I need them to know who he is. He’s not just a patient, he’s my son.

The thought of having to start over is stirring memories from when this all began. I’m afraid of having to start retelling my son’s story and reliving those dark and fearful days. But I’m also going to miss that light that lifted us from the darkness. I’m going to miss having her at our side.

We tell our son to be brave. To be grateful. To try to find the positive. And I am trying, but right now I just feel scared, and alone, and sad.