We need joy as we need air.

Maya Angelou

We need love as we need water.

We need each other as we need the earth we share.

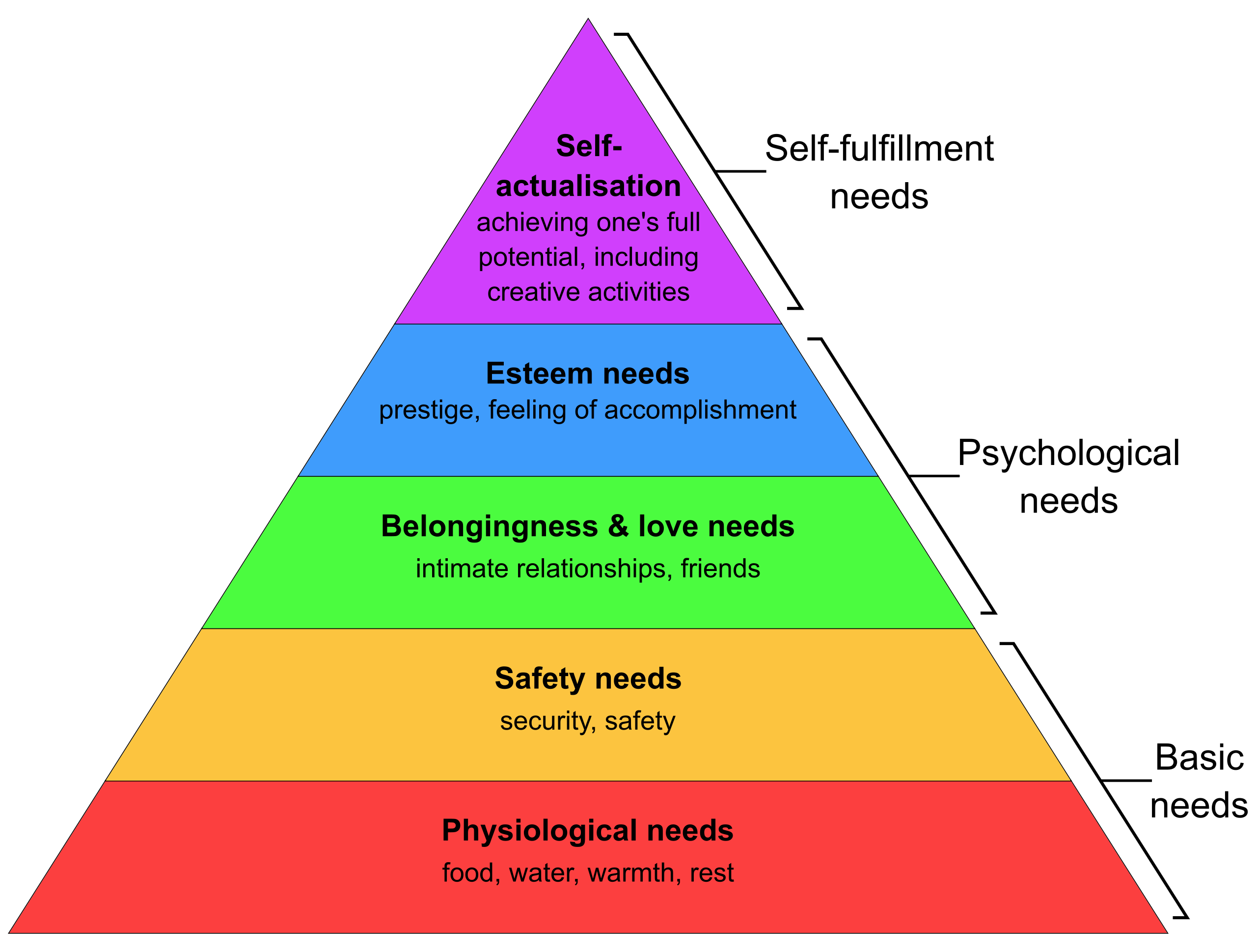

In psychology, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs depicts a five-tiered model of human needs: physiological, safety, love/belonging, esteem, and self-actualization. It’s often depicted as a pyramid with the idea that lower-level needs must be satisfied before higher-order needs can be fulfilled.

Growing up, my physiological needs were largely met. I had food, drink, and shelter. I was clothed with the finest sneakers from the grocery store and mismatched Underoos from Goodwill.

The next level, safety, is about order, predictability, and control. There wasn’t much of this in my childhood. I grew up in a different time, surrounded by a system that still believed in corporal punishment and people who were angry, frustrated, and mean. The lack of control, the fear of being punished, and the unpredictability of my environment made it impossible to feel safe.

If I was sad or scared and expressed my needs through crying, I never knew if I would be comforted, ignored, or told, “I’ll give you something to cry about.” The people around me couldn’t handle their feelings; mine were often too much, inconvenient, or wrong.

My safety level was never fully satisfied, so there was little hope for anything above that. My desire for love and belongingness conflicted with my need for safety, especially within my family. This is especially common with children and why people cling to abusive parents or partners. I had friends but never friendships, and giving and receiving love was confusing and dangerous.

Esteem is about the desire to be accepted and valued by others. It’s hard to feel worthy when you don’t feel like you belong, and it’s impossible to achieve self-actualization, the top level of needs, when you don’t believe you have any potential to become anything of significance.

Over the years, I tried many ways to make my needs important to have them met. I would put other’s needs above my own and do my best to satisfy them in hopes that they would do the same in return, but the people I surrounded myself with were only interested in having their needs met. If I did find someone willing to consider my needs, my programming reminded me that it was dangerous and that they wouldn’t be met anyway, so it would be better not to express them to avoid disappointment. I had a therapist who once told me that in a healthy relationship, there is room on the shelf for both persons’ needs, but I operated as if there was only room for one, and the needs on the shelf weren’t mine.

I’ve seen more and more how I interact with the world determines how my son interacts with the world. Whether it’s his desire to show his mother he loves her by heading straight to the flower section when we go to the grocery store or his unfortunate habit of not knowing when to stop a joke, I see what I do in him. I also know how the things that I don’t do but should do are absent from his behaviors.

I think about the example I am setting for my son. Even if he didn’t have special needs, I would want him to feel comfortable putting his needs out there and being surrounded by people who are willing and capable of meeting them. He deserves to know what a healthy relationship is and feel like an equal partner in these relationships rather than unworthy or afraid like I did. The reality is that he does have special needs, and he will be more dependent on others and will most likely be less able to navigate the world alone.

Change is hard, but there are so many ways in which our journey has already made me a better husband, better father, and better role model for my son. He already has the biggest heart and is sensitive to the needs of the people around him. I want to ensure he knows his needs are just as important and that he is worthy of having them met, too.