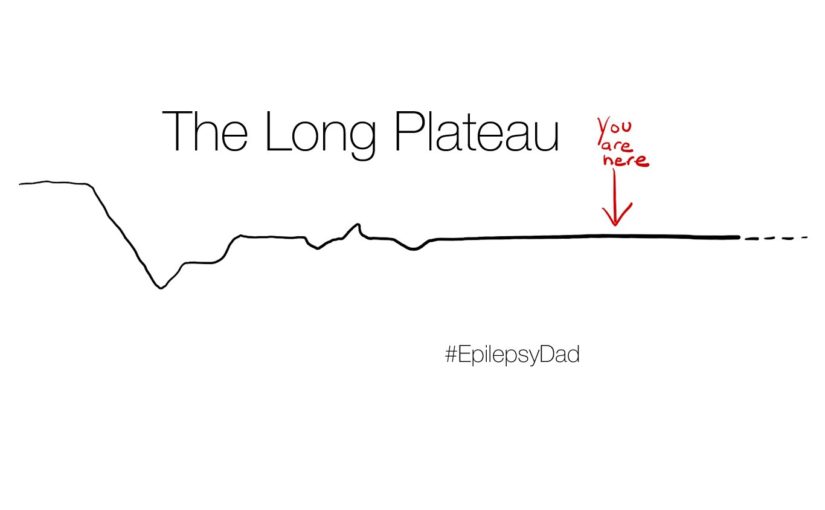

We are standing on a plateau.

For the past few years, my son’s condition has remained the same. He still seizes almost every day. He’s still on a handful of medication multiple times a day and the ketogenic diet. He still struggles in school and navigating relationships with his peers.

I should be grateful that he hasn’t gotten worse.

The beginning of our journey with epilepsy was the equivalent to falling off a cliff. We went from a normal childhood to fighting for his life in the matter of months. We went from school and friends to hospitals and doctors and nurses and therapists. We went from playing hockey to being toxic on medication and needing to be carried to the bathroom. Back then, I would have longed for things to stay the same.

Once he was stabilized, we spent the next few years trying to rebuild what he’d lost. Progress was agonizingly slow, especially as we discovered more pieces of him that could not be rebuilt. We stumbled every time we pretended that things were ever going to be like they were before. While we were no longer falling, the slope of ascent was so gradual that it was hard to tell if anything was getting better.

Eventually, some things did get better. There were fewer seizures, confined mostly to the early morning. He graduated from a handful of therapies. He stepped foot in school again. Some things did get better, but not back to where he was before that first seizure. And not any further.

Are we really plateauing or does it just feel that way? Are we doing everything we can to keep making progress or, like a person trying to lose weight, are we giving the appearance of doing everything but secretly skipping workouts or sneaking in extra calories? Or have we truly reached our limit of progress?

Years ago, when the direction of my son’s condition turned around, every day probably felt this way. I wondered whether things were as good as they would get, much like I’m doing now. I wondered if we were doing everything we could and whether we we doing everything right. I looked for someone to blame rather than accepting the reality of the situation. Because it’s impossible to believe that, no matter what you do, things will never be what you though they were going to be.

The longer things stay the same, the more I forget how far we’ve come. The more that “this is it” feeling takes over. The longer I sit in that feeling, the harder it is to hold on to hope for better.

And this plateau feels so long.