For the last few weeks, we’ve been temporarily living in Maine.

I love living in Philadelphia. But between being confined to the close quarters of a condo and the current tension in the city, we decided we needed space. While we are all working from home, this is also a rare opportunity where home can be wherever there is internet, and that includes the Pine Tree State.

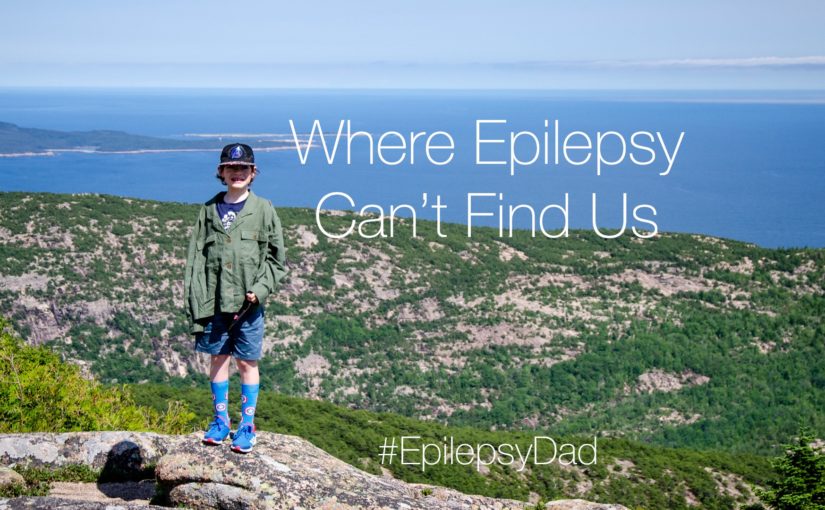

Whenever we go somewhere new, there is a part of me that wonders if it will be the place where epilepsy can’t find us. I wondered when we went back to Colorado. I wondered when we visited my family in Florida. But epilepsy found us in those places. I wondered again when we traveled further…to Hawaii…to Panama. But epilepsy found us there, too.

Still, as we took the 10 hour drive from Philadelphia, there was a part of me that still wondered. It wasn’t a good sign when my son drifted off to sleep in the back seat that a seizure work him from his nap. But we weren’t yet in Maine, though, so there was still hope.

As we pulled in to the driveway of the house we rented, I had a good feeling. The house was on a peninsula, surrounded by water on three sides. There were steps down to a rocky shore from the front of the house and a path down to a big, sandy beach from the back. There was a big yard for baseball, and trees blocking the view of any neighbors. We were secluded. Hidden. The sun was out. There was air…cool, salty, fresh air. Our getaway had everything we were looking for, and maybe the right ingredients to keep any seizures away, too.

When the first seizure came the next day, I chalked it up to exhaustion. The long drive and the late night exploring the house were the likely causes, and that shouldn’t be held against Maine. The seizures the next night were obviously caused by the long day spent in the water, fishing and finding shells and crabs. Our bodies just weren’t acclimated yet, so those seizures shouldn’t count, either.

But by the third day, and the fourth, and most days since, I haven’t been able to explain away the seizures. They happen after we are outside on a sunny day or after relaxing inside on a wet, foggy day. They happen after we go exploring and after we hang out watching a movie.

They happen because my son has intractable epilepsy.

Wherever we go, we won’t be able to hide from epilepsy because we take it with us. We pack it up like the bottles of seizure medication and the special ingredients for my son’s ketogenic diet. It finds room in the car no matter how little space is left after we tightly pack our belongings.

But even though I want to write a post like this every time we go to a new place, trying to hide from epilepsy is not the reason we travel and have adventures. We do them because our son is a fearless explorer. We do them because we can. We do them because we won’t let epilepsy and seizures limit the experiences we can give to our son.

There is nowhere we can go where epilepsy can’t find us.

But we will not let it stop us.