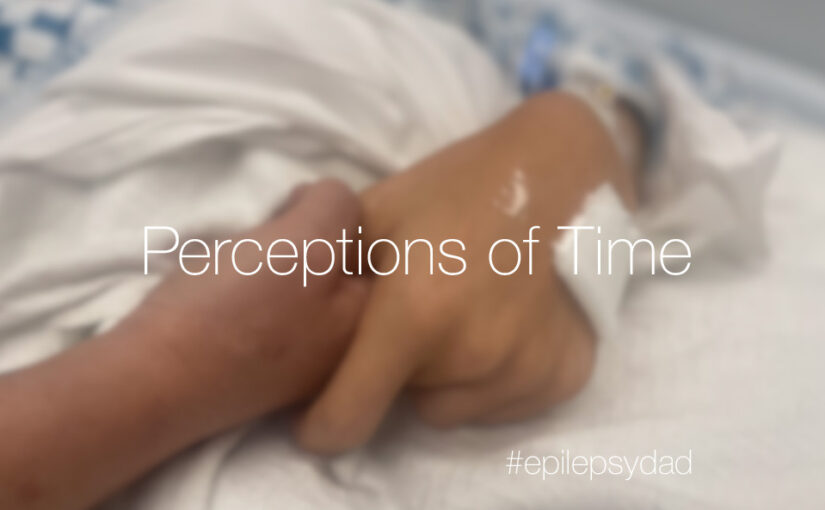

Last summer, I was at the pool with my son.

It wasn’t that long ago that he needed to stand on his tiptoes to keep his head above the water. Now, standing over six feet tall (the tallest in our family, as he likes to tell everyone), only his waist is submerged. His skinny torso sticks up like a twig in a pond.

His body carries many markers from his life. There are scars from his adventures and falls. There are stretch marks on his lower back from his growth spurt. And there are remnants from the incisions on his chest and neck from his surgeries that implanted the two devices and the leads to his brain.

It’s hard not to notice, prominently pushing against the skin on his chest, the two implants. Against that skinny frame, with no fat or muscle to buffer them, the devices look huge. They are a permanent alteration to the contours of his body, captured on his chest like a relief map, describing the differences in elevation and the way the land rises and falls. And similar to the permanence of mountains in our lifetime, they will remain a defining part of his body’s landscape.

Of all the recorded history on his body, the implants are the hardest for me to see. The scars, even those from his surgeries, can be rationalized away as everyday occurrences of a growing child. I’ve had a scar above my eye since I was five, when I chased my sister under a glass table and forgot to duck. I’ve had a scar under my chin from when I was ten and tried to jump over a softball on my bike. And I have scars on my hands and arms from the countless times that I clumsily pulled something from the oven without protection and burned myself.

But the implants can’t be explained away as normal consequences of living. They are more than just damaged or healing skin and tissue. They are unnatural, and there is no alternative explanation to the reality that they are devices inserted into his young body to help reduce his seizures. They are visible reminders of his challenges—challenges, like the devices themselves, that he will likely carry for the rest of his life.

Seeing them, it’s easy to fixate on the implications and miss out on the significance of the moments that they enable. He’s alive. He’s having fewer seizures and has stopped a few medications. He and I were in a pool playing basketball, spending time together, and laughing. The reason he has the devices may be overwhelming, but the life they allow him to live is a medical miracle.

I still see the devices when I look at him, but I’m learning to see them differently. They don’t just mark his struggle—they also mark his survival. They are symbols of how far medicine has come, of how far he has come, and of the moments we still get to share.